TWENTY years ago today marks the first case recorded of a disease that triggered an animal health and economic crisis which devastated agriculture and just about shut down tourism.

The outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease led to more than six million animals being slaughtered across the country, and tourism businesses losing millions of pounds.

Cumbria was the worst-affected area of the country, with 843 cases of a disease that ravaged the county for seven months.

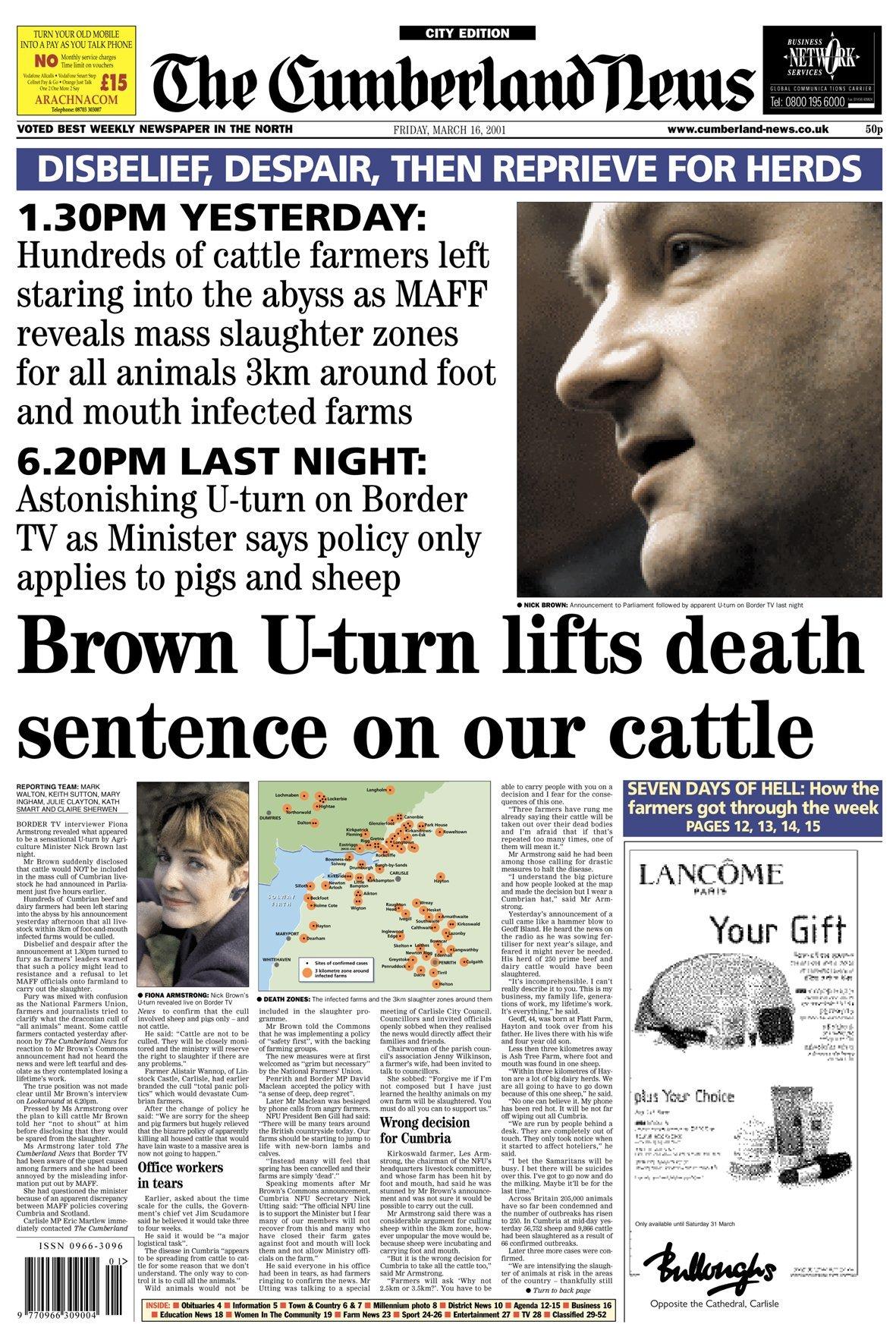

The pyres were everywhere: mounds of animals aflame in the countryside, the images burning across our news bulletins and front pages. Across the county, farms were fighting to beat back a virus that was swallowing up their livestock.

The images from those terrible months were shown around the world, and they are etched in the minds of every farmer, whether they lost their livestock or not.

The broadcaster Jon Snow wrote a piece for the Cumberland News a year after the events. He said: “Today, Cumbria is still seared upon my soul. Air crashes, road accidents, riots, the odd murder, nothing in 25 years of reporting domestic news had ever prepared me for the scale of human trauma that I experienced. It was unutterably brutal.”

Today, many key figures from the Cumbria fight-back from the foot-and-mouth outbreak reflect on how the county tackled the disease and why the current Covid pandemic feels all too familiar,

“There are parallels to be drawn between the FMD and Coronavirus crises – FMD is animal health and disease and Coronavirus is public health and disease. Both are epidemics that shut down sectors of society and the economy, and both have/had the same result of putting the country on a ‘war footing’, said Neil Hudson, MP for Penrith and The Border.

For Mr Hudson, the crisis was life-changing. He said: “FMD affected the whole country, but Cumbria was at the epicentre. It affected the farming and tourism industries and also other sectors like horseracing. Livestock could not be moved around the country. In Cumbria, 45 per cent of farms were subject to culls, and this rose to about 70 per cent of farms in the north of the county.

“I was deployed for a period on the front line as a temporary veterinary inspector during FMD in the south of Scotland. The reason I first started thinking of going into politics was on the back of these experiences. I felt after that I could use my professional background and experience to offer something in public life.

“Along with other veterinary colleagues from all parts of the profession, we were involved in disease surveillance and, sadly, supervising culls on farms. This was deeply upsetting being involved in the slaughter of so many animals. It was a life-changing time for me. This started me on my political journey. I am the only vet in the House of Commons. Standing up for the farming community and animal health and welfare is incredibly important to me as a vet and the MP for a rural and farming constituency.”

David Hall, National Farmers Union (NFU) north west regional director, said British farming had since recovered to become known globally for its leading standards of safety and traceability, a transformation testament to the lessons learned from foot-and-mouth and the resilience of British farming.

He said: “Technology has also moved on at a pace in the past 20 years. During the outbreak, faxing information to farms and ‘ringing around’ was commonplace, with no email or social media to fall back upon.

“We can communicate much quicker now than we did 20 years ago and it’s fair to say Government could implement a full lockdown on livestock movements almost immediately. We’re in the middle of a third national coronavirus lockdown now, so a lockdown of livestock ought to be a doddle in comparison. I do shudder though when I think about the role Twitter and Facebook would play if something like FMD affected the industry tomorrow. In hindsight, we were probably lucky not to have had it 20 years ago.”

Caz Graham is a broadcast journalist based in Cumbria. Over the past 15 years, she has become a familiar voice on BBC Radio 4 as a regular presenter of Farming Today, On Your Farm and other programmes including Open Country.

Speaking to The Cumberland News, Caz said: “For me, one of the most striking similarities between 2001’s FMD epidemic and today’s Covid pandemic is the way these two episodes made people feel. The scale of events in both cases was overwhelming and again, in both cases, there’s been a strong sense that those who were supposed to be in charge and on top of the situation were always two steps behind, making questionable decisions and detached from the truth. The reality of what the epidemic and pandemic really meant too little, too late.”

She added: “I think seeing just how raw foot-and-mouth still is for those who lived through it even now 20 years on, should give us a good idea of the impact the Covid pandemic is likely to have on the mental health of those who’ve been at the heart of this pandemic. The scars will be deep and take a very time to heal.”

As local slaughter teams could not keep pace with the number of animals involved, either having caught the disease or within the three-kilometre cull zones that were put in place, the Army was drafted in under the formidable leadership of Brigadier Alex Birtwhistle, who received a CBE for his efforts.

Moira Fisher and her husband, Robin, had the first confirmed case of foot-and-mouth in the county at their Smalmstown Farm, in Longtown, near Carlisle. Moira told Suzanne Elsworth, a freelance writer, who lives in Cockermouth, that the family didn’t realise the magnitude of what they were about to go through.“It was draconian,” adds Moira.“You couldn’t slaughter everything in a day and the pyres added to the pain. If it happened again, that would all be managed differently. As a livestock farmer, you give your animals a good life. This was so against everything we strive for.”

At Watchtree Nature Reserve near Great Orton, a former airbase near Carlisle, there is a stone inscribed as a memorial to the animals taken there in the biggest mass burial of the outbreak.“This was a blot on the landscape at the beginning,” said William Little, one of the team that founded Watchtree. “It was that place where they buried all those animals and we needed to take away that stigma. Now it’s an asset. Something good from something bad.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel